HISTORY OF BOARD TRACK RACING

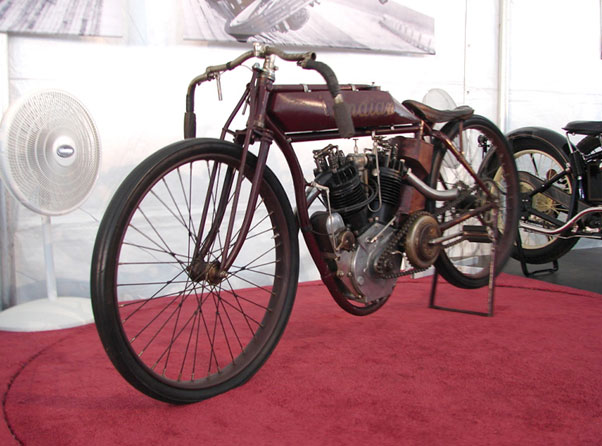

BOARD TRACK, or motordrome, racing was a type of motorsport, popular in the United States between the second and third decades of the 20th century, where competition was conducted on oval race courses with surfaces composed of wooden planks. Although the tracks most often used motorcycles, many different types of racing automobiles also competed, enough so as to see the majority of the 1920s American national championship races contested at such venues.

BY THE EARLY 1930S, board track racing had fallen out of favor, and into eventual obsolescence, due to both its perceived dangers and the high cost of maintenance of the wooden racing surfaces. However, several of its most notable aspects have continued to influence American motorsports philosophy to the present day, including: A technical emphasis on raw speed produced by the steep inclinations; ample track width to allow steady overtaking between competitors; and the development of extensive grandstands surrounding many of the courses.

THE FIRST BOARD TRACK opened at the Los Angeles Coliseum Motordome near Playa del Rey, California, on April 8, 1910. Based on and utilizing the same technology as the French velodromes used for bicycle races, the track and others like it were created with 2-inch (51 mm) x 4-inch (100 mm) boards, and banked up to 45°, and some venues, such as Fulford-by-the-Sea and Culver City, boasting unconfirmed higher bankings of 50° or more. Around a half dozen tracks up to two miles (3 km) long had opened by 1915. By 1931 there were 24 operating board tracks, including tracks in Beverly Hills, California, Atlantic City, New Jersey, Brooklyn, New York, and Laurel, Maryland. The board tracks popped up because of the ease of construction and the low cost of lumber.

END OF BOARD TRACKS

THE BANKING in the corners of board tracks started at 25° in 1911, like bicycles tracks were. The banking was increased until 60° was common. The effect of the banking was higher cornering speed and higher G-force on drivers. Fans sat on the top of the track looking down at the racers. When a driver lost control of a racecar in a corner, he could slip up off the track and into the crowd. An incident often killed a half-dozen competitors and spectators at a time. The velodrome at Nutley, New Jersey, a 1⁄8 mi (200 m) oval banked at 45° (generating lap times of 8 seconds or less) and built from 1 × 12 in (25 × 300 mm) lumber on edge, was "unquestionably the deadliest".

On September 8, 1912, Eddie Hasha was killed at the New Jersey Motordrome near Atlantic City. The accident killed 4 boys and injured 10 more people. The deaths made the front page of the New York Times. The press started calling the short 1/4 and 1/3 mile circuits "murderdromes". The 1913 motorcycle championship races were moved to a dirt track because dirt was safer. The national organization overseeing motorcycle racing on board tracks banned all competitions on board tracks shorter than 1-mile (1.6 km) in 1919.

BOARD TRACKS SLOWLY faded away in the 1920s and 1930s, though racing continued into 1940 at Coney Island Velodrome, Nutley, and Castle Hill Speedway in the Bronx. Notable driver fatalities on board tracks included four Indianapolis 500 winners, three of which occurred at the Altoona course in Tipton, Pennsylvania, and three in the same years in which the driver won at Indianapolis.

1919 "500" winner Howdy Wilcox died in an Altoona race on September 4, 1923, while co-1924 winner Joe Boyer and 1929 winner Ray Keech both suffered fatal accidents at the facility in the same years as their 500 wins, Keech's occurring only seventeen days after, on June 15, 1929. Gaston Chevrolet, winner of the 1920 Indianapolis 500, perished that same autumn, on November 25, 1920, at a Thanksgiving Day race at the Beverly Hills Speedway.

ANOTHER CONTRIBUTOR to the demise of board tracks was the expensive upkeep. Tracks needed new 2x4 boards every five years. During the last decade of board tracks, carpenters would repair the track from below after the cars raced down the straightaways at 120 mph (190 km/h). A further factor was that as speeds rose, overtaking became increasingly difficult; as long as it held together, the fastest car would almost always win the race.

This led to spectators turning their attention to the less-predictable racing taking place on dirt tracks.